Set off in search of breakfast this morning, but it didn’t get off to a very good start. We couldn’t find anywhere like the kinds of places we’ve grown used to – little restaurants where locals slurp broth. We were both still feeling a bit jangled, and Virle’s cough hadn’t got much better overnight, and all in all we were not the happiest of bunnies.

And the streets here are pretty challenging. There are to all intents and purposes no pavements. They exist, but they’re used for parking, and are literally unusable by pedestrians. So you’ve no choice but to walk out in the anarchy of the road, where vast Chelsea tractors, delivery vehicles, scooters and tuk tuks jostle for position and weave past each other in totally unpredictable ways. Crossing the road is a gamble every time, involving guesswork, nimble footwork and a lot of hopework. Not really the ideal start to the day when you’re not feeling that ticketyboo, and you’ve got nothing in your stomach.

Eventually we found a place that looked right, and sat down, and ordered two plates of noodle soup – V a ‘pork combination’, and me the ‘special’, neither of us with any real idea what we’d get – and within no more than a minute, two steaming bowls of broth appeared. “Is this what we ordered?” I asked. The guy looked baffled. Understandably. Many people round here speak little or no English. Our waitress reappeared. “Is this what we ordered?” I asked again. “We ordered different things, but these look identical.” I’m not sure she quite understood, but she looked at what we’d been given, reached down, and put Virle’s bowl in front of me and vice versa. They still looked identical, but they were now apparently at least the right way round.

Anyway, they were very tasty, and did the job just fine, and we were in much improved spirits when we headed back toward the barber we’d encountered last night. As luck would have it, he was sitting idle when we arrived. I reminded him that we’d said we would return, and confirmed “Three dollars?” Yes. Three dollars. Right, good. So he got to work, gave me a good cut, if a little closer than I’m used to, and gestured did I want ‘zero’ for my beard. No, not zero. One then, he decided, and set to, again taking off a lot more than I generally would, but fine, it’ll grow back. Virle gave him a five. He said thank you. I said can I have the change please. He looked baffled. I said we agreed three dollars. He gestured at my beard. I got my translation app out, and translated “If you want to charge more for the beard, you should say so before you start.” He made a sort of fair enough gesture, asked around a couple of neighbour stalls, and ended up handing me a 5,000 riel note. Equals $1.25. Ok. Whatever.

I’m sure it sounds really cheap to be quibbling over a couple of dollars, but along the lines of yesterday’s grumbles, we really didn’t come across this kind of thing before we hit Cambodia. And I for one find it a bit lowering. Do as you would be done by, innit. I don’t make explicit in-so-many-words agreements with other people and then renege on them, and it does piss me off when people do it to me.

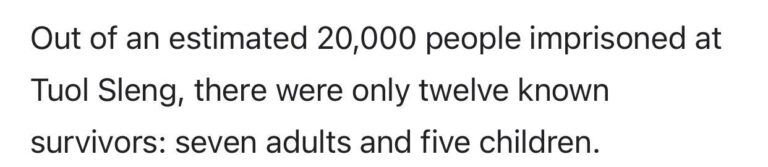

And then we went to the Genocide Museum. And all of that suddenly looked as peevish and petty as it doubtless does to you.

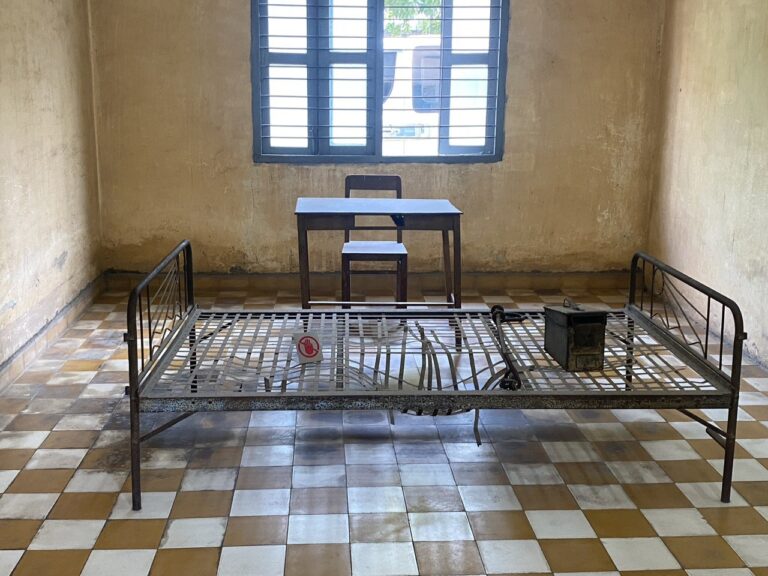

The place had been a school. On the groundfloor of the first block we entered, crude doorways had been knocked betweeen the old schoolrooms, each of which had been filled with crudely built cells, each maybe eight or nine feet long by three wide. No furniture. Just a tile-floored space. Room after room of them. On the floor above, the same, except constructed in wood. And above that, the original schoolrooms with no partitions, where prisoners were kept chained in rows, like the notorious pictures of slave ships. Barbed wire and bars ‘to prevent escape and suicide’.

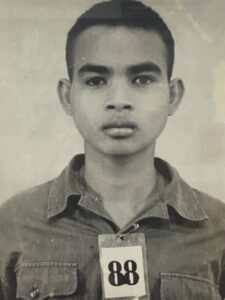

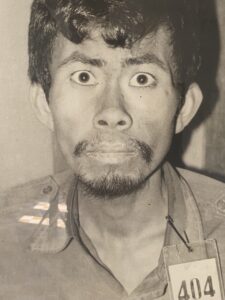

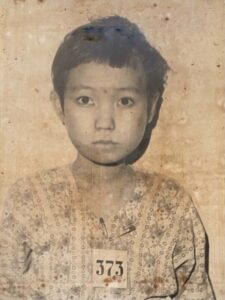

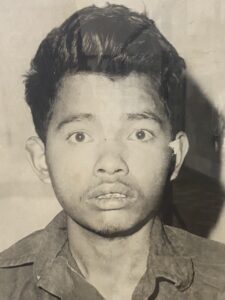

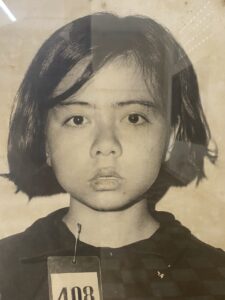

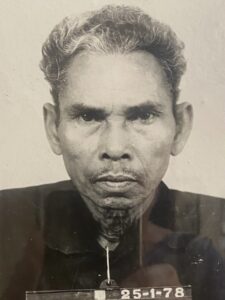

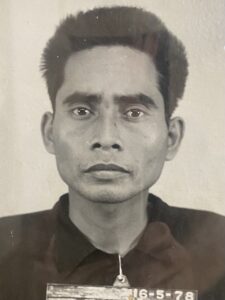

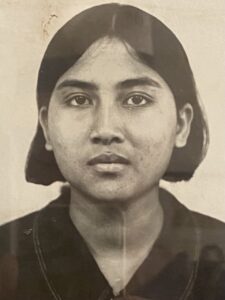

In other blocks, display after display of haunting photos, portraits mostly, record shots of ordinary people of all ages, suddenly taken out of their lives and finding themselves in this new one.

Hundreds upon hundreds of them. What can you say that doesn’t sound trite. Nothing comes to mind. Let their portraits speak for them.

Cabinets full of skulls…somehow, obscenely, almost robbed of their power to shock by a thousand representations, from concentration camp to silver screen. But then the arresting sight of a cabinet full of, what?, ribs? Somehow all the more jarring by their sheer profusion and cluttered anonymity. How many lives jumbled together in this modest little box of glass and wood.